Mat Messerschmidt

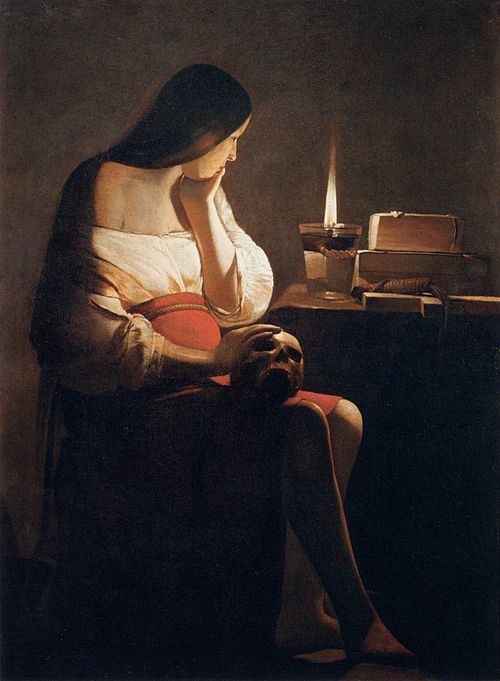

Death, Desire, and the Human Body

In his 1927 Being and Time, Martin Heidegger depicts a comportment of authenticity towards the reality of our death as central to the general task of living authentically on earth.[1] If you do not live your death, so to speak, as the horizon of your life, then you are not living authentically. Most people, especially in modernity, do not achieve this authenticity, which Heidegger calls “authentic being-towards-death [Sein zum Tode].” To the contrary, they live their lives in the frantic evasion of death.

Anyone in the market for a profound philosophical reflection on the topic of death should not pass by Being and Time. Yet it seems to me that a well-discussed omission in Heidegger’s thought is perhaps most blaring precisely in his contemplations of being-towards-death. Heidegger is notorious for his lack of philosophical attention to the human body – and his sense of authentic being-towards-death never seems to involve reflection on the death of the body, the death of our “mortal coil.”[2] From the standpoint of phenomenology, the philosophical approach that claims to start from human experience, this seems to me to be problematic. We experience death – our own imagined death, or the deaths of others – as the death of the body, and our movement towards death is experienced as the decline of the body, as aging. Our consciousness of our bodies, in short, is central to the way we experience death in our world.

What, then, does it really mean to confront death authentically, if Heidegger’s answer to the question is not enough? How can we reconfigure our sense of what “authentic being-towards-death” should mean in a way that takes account of our bodies, of our existence as fundamentally embodied beings?

To think of our bodies, the Western philosophical and theological traditions have long recognized, is to think of our finitude. The mortality of the body is juxtaposed to the immortality of the soul. But we inhabitants of modernity do not all believe in the immortality of the soul. Does the body then still merit the status of the bearer of our fundamental limitation? Yes, because there is another reason to associate the body with human finitude, with human limitation: our flesh is constitutively desirous, even founded in desire, and the desirous flesh never finally rests content, never ultimately achieves satisfaction. We eat to slake hunger; we have sex to satisfy our libido, and then, after a brief period of contentment, the cycle begins again. “Self-consciousness is desire itself [Selbstbewusstsein ist Begierde überhaupt],” said Hegel in 1807.[3] It is my sense that Hegel believed that there could be a happy ending to the “desire” that founds us, that it could find some sort of ultimate satisfaction, but this sort of optimism is ancient history by Heidegger’s time. Jean-Paul Sartre claims in his 1943 Being and Nothingness that the human being is desire – unending, tragically unquenchable desire. This sentiment is memorably summed up in the assertion that the human being is a “useless passion.”[4] The extent to which we are embodied, the extent to which we are bodies, is the extent to which we are eternal lack, eternal missing-ness.

What does this have to do with death? It has more to do with death than Sartre’s book acknowledges, I think, and here I insist upon following a thread embedded in his thought that he himself does not much pursue. The body grounds a “world of desire” and lives in, or as, the center of this world. [5] The satisfaction of our desires means a momentary cessation of this or that desire among the totality of our desires – a totality which, again, is all we are. This means that, in a sense, the satisfaction of desire is the end of the human being that is only desire – or, to put things more precisely, the degree to which desire finds satisfaction is the degree to which the human being meets its end. This, says Sartre, is why “sensual pleasure is so often linked with death.”[6] We all strive after the final and complete satisfaction of desire: Sartre calls this the “project [of] being God.”[7] Of course, for the “useless passions” that we are, this is an impossible project, so there is never any literal death via satisfaction. Yet, by the logic just articulated linking pleasure with death, the success of this project would be the same thing as death, if it were ever to be realized. This view yields a timelessly tragic view of human life: with every heartbeat, we desire, and with every step toward the satisfaction of our desires, we take a step in the direction of death. One might be reminded, in a distant way, of another early-1900s theorist of the erotic, Sigmund Freud, who insisted upon the proximity of eros and thanatos.[8]

To take these reflections in a different direction than Sartre does, I would suggest that we can arrive at the following emendation to Heidegger’s articulation of authentic being-towards-death: authentic being-towards-death means living in the authentic consciousness that death is the law written into the fabric of the desiring body. Our body’s yearning is its intimacy with death; its desire is coextensive with its mortality. We find a related sentiment, I believe, in the thought of yet another thinker who is, like Sartre and sometimes Heidegger, labeled an existentialist. Friedrich Nietzsche claims that all life is “will to power.”[9] In explicating this all-important Nietzschean phrase, French scholar Eric Blondel tells us that, for Nietzsche, “the world is desire,” and that a “tragic” and eternal gap between desire and its final fulfillment can be read into the word “to,” which forever separates the desire implicit in “will” and the satisfaction implicit in “power.”[10] Every act of striving thus affirms both our desire and our limitations. The final achievement of satisfaction on earth, the final achievement of “power,” would spell the end of the human being, understood as will to power, if it could ever be accomplished.

But there is another way to imagine the unraveling of the “useless passion” that we are, other than to think of the extinguishing of that passion via its satisfaction. What if this passion simply stopped striving, simply became passionless? What if, in other words, desire simply ceased its desiring, and became listlessness? This would also, on Sartre’s view of things, be the death of the human being. It is also what Nietzsche calls “nihilism” when it occurs on a broad social level: nihilism is a broad cultural “failure of desire,”[11] or erotic failure.

This form of mortality, in which desire does not negate itself in satisfaction but simply goes slack, seems to be a much more real and literal form: the weakening of desire is in fact a common way in which we tangibly experience our mortality. We no longer want to run five miles in the morning; we lose the motivation to stay up until 3am to put the finishing touches on a brilliant piece of writing; we become less competitive; our sex drive wanes. The French called orgasm the “little death” according to a Sartrean logic – the end of desire presages the end of the human being – but the inability to achieve an erection could be called the same thing. It is a reminder of the body’s aging, its movement towards death, as a sign of the fading of desire’s power.

I have been speaking toward this claim: authentically acknowledging the sign of one’s death in all the desirous body’s signs of decline or limitation must be a part of authentic being-towards-death. Heidegger is blind to this element of truly authentic being-towards-death. Could it be that Heidegger himself could not summon the courage to confront the death of the body? He was 42 years old at the time of the publication of Being and Time, in the early years of middle age. Heidegger admittedly records no erectile difficulties, but he was old enough to have felt the thrill of morning hikes and cross-country skiing in the Black Forest start to give way to sore limbs and longer recovery times. Could it be that Being and Time theoretically omits this tremendously important element of authentic being-towards-death – the confrontation with the decline and death of the body – because it was the element its author found most difficult to confront? It is impossible to answer this question confidently in the affirmative, but if every philosophy is the personal confession of its author, as Nietzsche says, then certainly remarkable omissions must confess something, as well.[12]

One final thought on Heidegger’s view of death, and its place within the Western history of thought, which he is forever summing up for us. We can surmise that the atheist and largely anti-Christian philosopher saw the Christian belief in the afterlife as a flight from authentic being-towards-death. It must be said, however, that the Christian tradition often shows more sobriety than Heidegger himself does toward the relationship between the concupiscence of the human flesh and mortality. St. Augustine, for instance, differentiates the city of God from the city of men in the following way. The damned city of men cannot look beyond this life, for, “liv[ing] after the flesh,”[13] that city believes in the final satisfaction of desires in this world: “the earthly city is dedicated in this world in which it is built, for in this world it finds the end toward which it aims and aspires.”[14] It is because the city of God believes in no such satisfaction that it can look beyond this world, living “like a captive and stranger” here, viewing every moment in this world as a moment in a cage that is poised to pass away.[15] For Augustine, too, then, the tragic trajectory of earthly desire is the mark of our human finitude, the mark of our mortality, and at the heart of what it means to be a human being. If this is not an enduring Western conviction regarding the being of the human being, it is at least a recurring one.

[1] Martin Heidegger, Sein und Zeit. 19th edition. Max Niemeyer: Tübingen 2006, 249-267.

All Heidegger, Hegel, and Nietzsche translations are my own.

[2] William Shakespeare, Hamlet 3.1.68. The phrase is from Hamlet’s “To be or not to be” soliloquy.

[3] G.W.F. Hegel, Phänomenologie des Geistes. 14th edition. Suhrkamp: Frankfurt a.M. 2017, 139.

[4] Jean-Paul Sartre, Being and Nothingness. Trans. Hazel E. Barnes. Washington Square: New York 1984, 491.

[5] Sartre, Being and Nothingness 510.

[6] Sartre, Being and Nothingness 510.

[7] Sartre, Being and Nothingness 724.

[8] See, for instance, chapter 6 of Civilization and its Discontents (Sigmund Freund, Civilization and its Discontents. Trans. James Strachey. Norton: New York 2010, 103-111).

[9] Friedrich Nietzsche, Jenseits von Gut und Böse. In Sämtliche Werke: Kritische Studienausgabe in 15 Bänden. 9th edition. Ed. Giorgio Colli and Mazzino Montinari. De Gruyter: Munich 2007, 208. He claims that the will to power is a “basic organic function,” and that it is the “primordial fact of all history.”

[10] Eric Blondel, Nietzsche: The Body and Culture. Trans. Sean Hand. Stanford: Stanford University Press 1991, 47.

[11] This is Robert Pippin’s phrase to describe Nietzsche’s nihilism (Robert Pippin, Nietzsche, Psychology, First Philosophy. University of Chicago Press: Chicago 2010, 54).

[12] Nietzsche, Jenseits von Gut und Böse 19.

[13] Augustine of Hippo, The City of God, trans. Marcus Dods. Hendrickson Publishers, Peabody, MA 2009), 456.

[14] Augustine of Hippo, The City of God 452.

[15] Augustine of Hippo, The City of God 628.

INDICAȚII DE CITARE

Mat Messerschmidt ,,Death, Desire, and the Human Body’’ în Anthropos. Revista de filosofie, arte și umanioare nr. 10 / 2025

Acest articol este protejat de legea drepturilor de autor; orice reproducere / preluare integrală sau parțială, fără indicarea sursei, este strict interzisă.